Review: Orson Welles’ Lost Film ‘The Other Side of the Wind’ Finally Found — On Netflix, Of All Places

Netflix has so thoroughly taken over the movie business they even have the dead directors working for them now. Orson Welles passed away in 1985, but there his name is up on the screen (or down on the screen if, God help you, you watch this movie on your phone). It’s smack dab in the middle of one of the most surreal phrases I have ever encountered in a movie theater: “Netflix presents ... An Orson Welles Picture.”

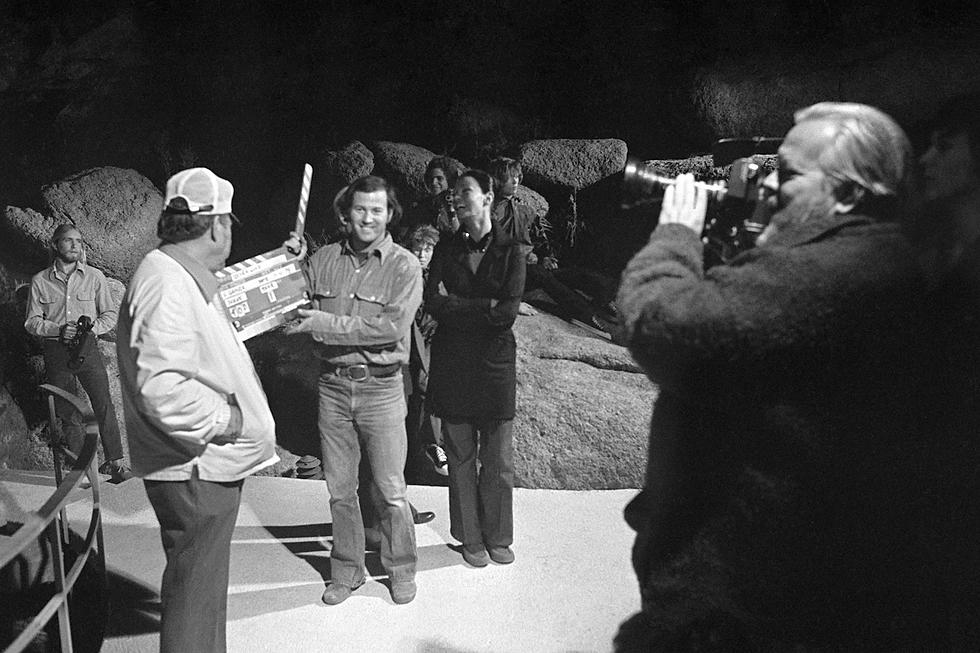

That title card sets an appropriately disorienting tone for the picture to follow. It has been assembled from some 100 hours of raw footage, using Welles’ notes and rough cut of some sequences, by a team of producers and editors who claim they have set out to fulfill Welles’ original vision for The Other Side of the Wind. Welles shot the film off and on throughout the 1970s as his financial fortunes waxed and waned. And the finally finished product does certainly resemble Welles’ completed films — aesthetically, it looks a lot like his documentary F For Fake, completed around the same period, and thematically it has all kinds of resonances with Citizen Kane — even if it’s a lot less precise (and sometimes a whole lot sillier) than his masterpieces.

Kane is an interesting reference point for this film. Filmed in 1941 when Welles was just 25 years old, it could be described as a young man’s vision of who he was afraid he might become. Then, 30 years later, Welles made The Other Side of the Wind, a self-lacerating critique of the man he became. Kane is about a billionaire media magnate; Wind is about a penniless artist. But both try to burrow into their central character from the outside in, compiling a portrait of a singular figure from many different perspectives. And both pursue the elusive truth at the center of a man’s soul.

Whether or not you think The Other Side of the Wind actually finds anything profound to say in the midst of that pursuit will probably depend on how much you can get on The Other Side of the Wind’s quirky wavelength. I’m guessing most audiences who actually sit through it will be split — and that at least 7 out of 10 people who start it on Netflix will turn it off after the first 20 minutes unless they know in advance from reading a piece like this one that the movie contains extensive and graphic female nudity.

Yes, The Other Side of the Wind is also Welles’ most sexually explicit project (unless my memory of Transformers: The Movie is very incomplete). Here’s how it works: The movie we are watching called The Other Side of the Wind is supposedly a documentary about the final day in the life of a difficult, brilliant, down-on-his-luck director named Jake Hannaford (John Huston). Hannaford is throwing a party to screen his latest, as-yet-unfinished film, which is also called The Other Side of the Wind, and he’s invited an assortment of journalists, writers, and showbiz urchins to follow him around and record every single second. So this “documentary” is cut together from that footage and interspersed with scenes from Hannaford’s The Other Side of the Wind, a piece of arty sexploitation that seems like Welles’ riff on (and also his parody of) both ’70s porn and the rough-hewn abstractions of the New Hollywood era’s most fanciful productions.

Hannaford’s movie — which is about a mute and frequently naked Native American woman (played by Oja Kodar, Welles’ co-writer on the project) pursuing a man through a deserted landscape — is alternately ethereally gorgeous and laughably terrible. Perhaps this was part of Welles’ design. Hannaford’s movie is in trouble. The director has Wellesian money issues of his own. His leading man (played by the ideally named Bob Random) abandoned his role midway through shooting. The Other Side of the Wind — make that both Other Side of the Winds — may never be completed. If the film within a film looked like a masterpiece, the movie we are watching wouldn’t make sense.

It might be a little more entertaining to watch, though. As a depiction of a once-great artist in creative and emotional free fall, The Other Side of the Wind might be a little too effective. Huston looks appropriate grizzled (grizzled is my polite way of saying he looks awful) and his screening party is a claustrophobic nightmare of booze and bickering. The only “escape” are the scenes in the desert between Kodar and Random, which are bizarre and off-putting. Clocking in at a full two hours, the cumulative effect is disorienting. After a while, I just wanted to get out of that party (and away from Kodar).

That doesn’t mean that I wasn’t glad I saw the film, or that I don’t admire the massive financial and creative undertaking that went into completing this long-lost production. The edges are certainly rough; the sound quality changes from line to line and occasionally from word to word. But a lot of that works into the film’s mixed-media approach, and to its overall mood of a life that is rapidly falling apart, held together by a thread that is unraveling before our very eyes.

The Other Side of the Wind plays tomorrow at the New York Film Festival. It premieres on Netflix on November 2.

More From Newstalk 860